Broken windows, shattered glass littering the street. Battered cars, some overturned. Looting. Anarchy. A haunting symphony of gunshots, explosions, and screaming into the night. The faint orange glow of flames emanating from the horizon.

If someone were to ask you what a world without police would look like, chances are that these are some of the many dystopian images that may come to mind. After all, police have become an established part of modern society, omnipresent in media and daily life. Why would you ever want to get rid of them?

It would be equally, if not more ridiculous, however, to assume that a world without police would be a simple paradise of community dinners, loving our neighbours, holding hands and singing songs until sunrise. Violence and deviant behaviour exist whether we like it or not — if such a world were to ever exist, simply removing police without changing anything else would not be the way to reach it.

What is common in both of these lines of thought, though, is that they aren’t based in reality. Some may consider our current reality as a lot closer to this utopian vision, perhaps owing to police presence in some way. Others may consider police as contributing to real-world versions of the aforementioned dystopia. Is the continued faith that we collectively place in the existence of policing not utopian already? How much crime does it actually solve?

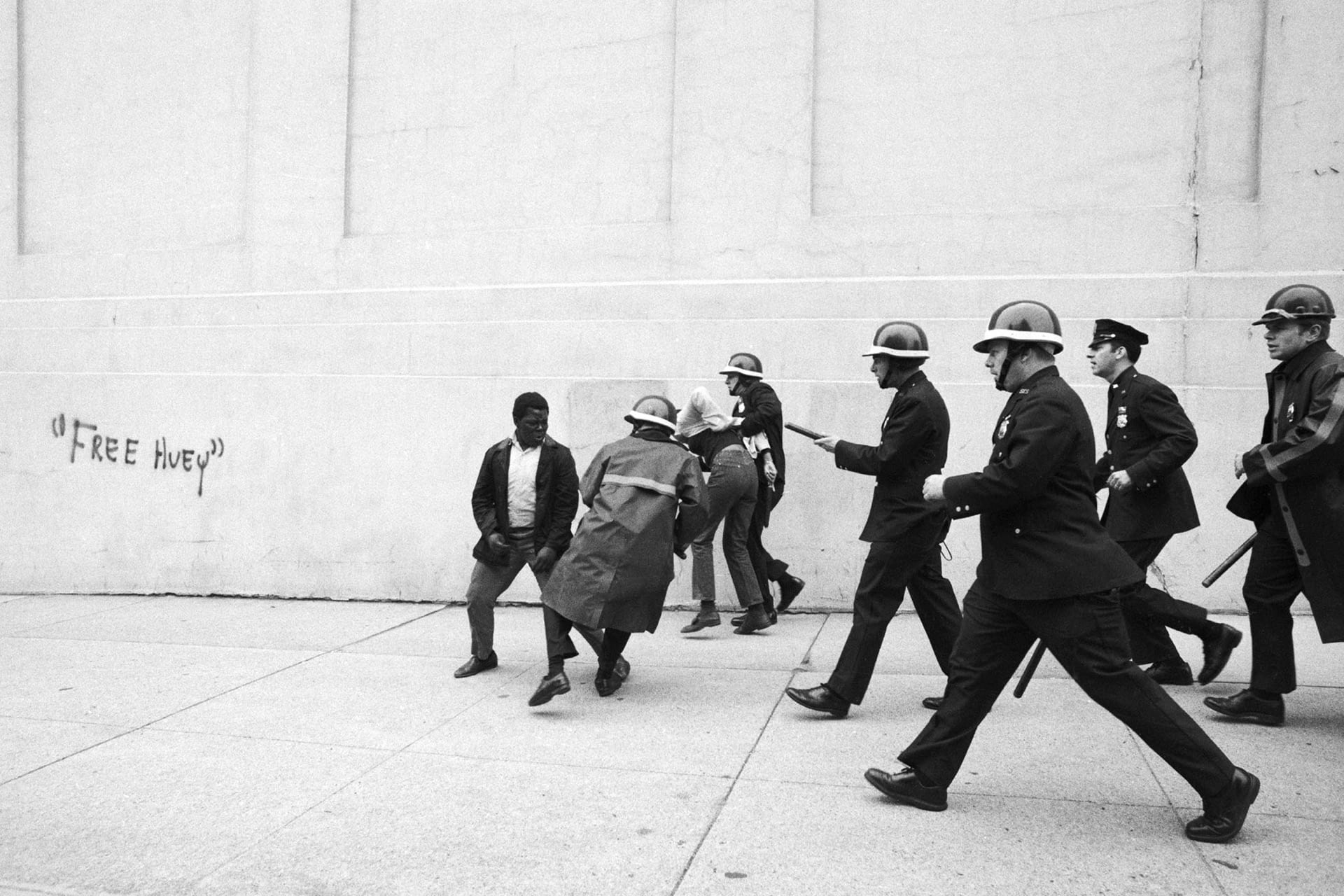

In the wake of persistent high-profile cases of police brutality and racial injustice across the Western world, what was once considered a fringe movement of unrealistic individuals has gained serious traction in recent years. Individuals in favour of abolishing the police have become far more present in mainstream discourse — as violence continues to balloon and racial tensions are continuously inflamed by police presence, the desire for alternatives grows. More than just offering hollow or idealistic condemnations of any form of authority, numerous well-respected authors have made serious arguments as to why and how we should remove the police from our societies.

Even if you are the most staunch anti-police advocate, convincing others to get rid of the institution still requires a baseline level of pragmatism. Providing certain pieces of evidence, such as that there being little to no correlation between increased expenditure in policing and reduction in crimes or violence, may just bring about the familiar refrain of ‘why not just reform them instead?’

The main obstacle to adopting more abolitionist views is not because there is no justification to get rid of police — many authors have outlined convincing reasoning for the ‘why’ questions. The problem is that these reasons have yet to fully trickle into mainstream thought. Poor communication also plays into After all, why hold on to a system that is institutionally unwilling to be repaired? By examining one dimension of contemporary police work that may be more relevant to

What is clear is that the discourse surrounding policing is fundamentally dominated by fear — either a fear of police or fear without police. Though it is certainly a powerful motivator, fear fundamentally has no place in policymaking. As an exercise in moving beyond fear and beyond impossibly utopian or dystopian imaginations, examining the function of currently operating alternatives to police can help us move forward the conversation past its current political roadblock. Examining evidence-driven, trauma-informed practices in the real world can help bridge the gap between total fear toward positive and realistic change.

Violence as a public health issue

There are so many roles that police take on that it is important to make sure all parties involved in the conversation have the same understanding of what is being referred to. Are they primarily for enforcing the law? Monitoring traffic incidents? Investigating crime? Patrolling the streets?

In the popular imagination, one of policing’s main functions is to not only provide ‘law and order’, but ‘to protect and serve’. After all, what is the motivation for the presence of police if not for the continued existence of violence in our communities?

Yet whose violence do we tolerate? A thousand people are killed by police every year in the United States, with Black people being three times as likely to be murdered by officers. This wake of death and thousands more broken families facilitates systemic racism and a fear of police that continually feeds into itself. Are police actually protecting or serving the common good?

Violence is a major part of the pervasive culture of fear that continues to perpetuate and justify the existence of policing. So long as violence remains a relevant concern, it will prevent large-scale organizing for alternatives — it frames the debate against abolitionists as people who want a decrease in overall safety and an increase in violence.

Within this context, several organizations have emerged as a means of getting to the socio-economic root of violence within communities. Rather than policing’s reactive approach to violence, these ‘violence reduction programs’ emphasize a public health model to violence – viewing violence as something that can be treated like an illness rather than deviant behaviour that needs to be swiftly punished.

Based on a scientific, evidence-based method, the public health model of violence prevention generally consists of three main steps.

- defining and monitoring the problem (who, what, where, when, and how?)

- identifying risks and protective factors

- developing and testing prevention strategies

One of the most prominent organization within this field is CURE Violence. Beginning in Chicago in 2000, their pioneering approach to reducing violence quickly expanded to other major cities throughout the United States and then worldwide.

At a practical level, CURE’s operations include both short-term and long-term solutions via ‘violence interrupters’ and outreach workers. Violence interrupters provide immediate conflict resolution in cases of domestic dispute. Trained in trauma-informed care and de-escalation tactics, they practice mediation in the field separate from the police. On the other hand, outreach workers work to build long-term solutions, constructing networks with various stakeholders in a community that may be afflicted by violence.

Charles Ransford, director of science and policy at CURE Violence, describes the organization’s long-term vision of society where, “communities will have sufficient violence prevention resources for community-based interventions, as well as school-based and hospital-based, as needed. There would also be sufficient support services, such as mental health, trauma treatment, employment services, and education.”

Another organization that has taken some of these public-health oriented conclusions and applied them to a different context is the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit (SVRU). Based in Glasgow, the organization began as a small subsect of the police department and subsequently grew into something much larger. “The currently utilized methods of crime reduction don’t work. Full stop. Let’s be honest about this,” says Will Linden, deputy head of the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit. Operating similar programs as CURE — ‘navigators’ function to outreach workers — when they were introduced in 2005, the city of Glasgow alone was considered the ‘murder capital’ of the world. Since they were founded, the SVRU reduced rates of violence by 41% in Glasgow and 35% nationwide.

A major component that drives the public health-oriented violence solutions is the desire to move beyond reactive solutions. “It’s about taking the public health methodology and taking it to the street-level in order to see what are the drivers,” says Will Linden. “Because what we know is unless you’re tackling those drivers, all you’re doing is you’re patching it up. You’re not really fixing the problem – you’re just basically sticking a band-aid on it. It’s about getting beyond that band-aid, and that’s what outreach workers do.”

Both organizations cite the lack of funding as the most significant obstacle to their program. “Most sites struggle with insufficient staff for the level of violence they are facing. It costs a lot more to incarcerate a person than it does to change their behaviors, but it is hard to get people to understand and support that,” says Ransford.

How do these programs respond to skepticism and difficulties from public stakeholders? Fear of diverting resources away from policing continues to scare off potential allies of these programs. On this front, Ransford states that these concerns are frequently overblown: “Cure Violence sites typically receive less than 1% of the funding that police departments receive. Funding for this work is not even in the same ballpark as police funding.”

“Ultimately,” he says, “city budgets reflect the priorities of a city. The important question that should be asked is whether cities are properly prioritizing preventing violence and keeping their communities safe. The [violence prevention] approach has been evaluated and shown to be effective at saving lives. It should not be a difficult decision to invest in an approach that works.”

Violence interruption: a potential path to abolition

The evidence for public-health violence-reduction models are promising – anyone honestly seeking a pragmatic solution to the issue of violence should be able to look at these programs and see that they provide substantial reduction for a fraction of the cost of police.

From an abolitionist perspective, however, there are several causes for concern with this model. Firstly, these programs’ connection to current police infrastructure could be problematic if they continue to grow. Ransford emphasizes that while CURE’s work is fundamentally different from law enforcement, the two groups have a working relationship, albeit a complicated one; CURE receives information from the police regarding crime statistics, which allows them to identify at-risk areas. Though there is occasional collaboration, violence interruption workers and outreach teams like CURE’s have been subjected to police harassment and even detainment.

The SVRU functions under a similarly complicated umbrella within the police — if the SVRU is unsuccessful in a given circumstance, the police are sent in. “We are also funded fully by the Scottish government”, says Linden, “so we sit somewhere in between [police and alternative].”

While some abolitionists may say that this connection is enough to write off violence reduction approaches altogether, the existence of tensions between the two nonetheless shows that they can be separate institutions. Will Linden describes this complicated relationship, saying: “Sometimes we clash with policing, sometimes we clash with government. We are friendly to both and also not so friendly to either as well, depending on where we sit. Both of the organizations love us when we’re a success, and when we have problems, they run away from us like every other organization.”

VRUs and public health units have and could continue to become integrated within current policing institutions. Playing up these tensions and guaranteeing VRU separateness moving forward is arguably necessary. “Policing can’t really instruct us on what to do – we’re an outside body existing within policing where we have our own structures.” By maintaining this institutional freedom, this could be both its greatest strength and most effective way of gaining popular support.

Abolitionist thought is also at odds with tendencies to reform or ‘rehabilitate’ what they view as an inherently corrupt institution — rather than a ‘few bad apples spoiling the bunch’, they understand the tree itself as rotten to its roots. Within this framework, a ‘few good apples’ are an aberration rather than the norm.

Many of these concerns are well-founded; the question of how far do reforms and rehabilitations go is a necessary one to answer. If officers need to be given body cameras to prevent abuses of power, the likes of which they might even turn off without consequence, what is the point of injecting so much money into that infrastructure?

Body cameras are pointed to as one of a series of ‘reformist reforms’ — proposed solutions that do little to materially address the primary root causes of violence, but instead expand current police capacity. As another example, while ‘community policing’ and other ‘neighbourhood watch’ oriented initiatives sound like a way of reducing tensions, according to some critics, they have historically allowed for a further entrenchment of police misconduct. By allowing the growth of personal relationships between police and community members, it not only may allow for police to further target and profile individuals based on information gained in confidence, but it may at the same time shield officers from criticism based on the establishment of personal relations with community members.

In this context, violence reduction approaches could be interpreted by some as a form of ‘community policing’, considered a ‘reformist reform’ by abolitionists. It doesn’t have to be this way, though — ensuring separation of these organizations from policing as they grow can make it such that information and community relationships are not exploited for use by an institution whose focus is on punishment. Linden refers to the SVRU’s approach as fundamentally based on ‘community consensus’ as opposed to external policing by force; being part of and trusted by the community hinges on integration within it at all times. Superficial ‘community relations’ operations that are focussed on surveillance and intelligence gathering are part of the problem.

“It’s about taking the public health methodology and taking it to the street-level in order to see what are the drivers,” says Will Linden, deputy head of the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit. “Because what we know is unless you’re tackling those drivers, all you’re doing is you’re patching it up. You’re not really fixing the problem – you’re just basically sticking a band-aid on it. It’s about getting beyond that band-aid, and that’s what outreach workers do.”

Another main concern with violence reduction solutions is making sure that they aren’t just focussed on ‘pathologizing’ the problem, treating violence strictly as an individualized, isolated phenomenon with a one-size-fits-all ‘cure’. A core practice that should be at the centre of scaled-up solutions, according to Linden, are those that are mindful of social justice, emphasizing that the simultaneous funding of other socio-economic opportunities is necessary. Both abolitionism and the SVRU’s philosophy are in alignment on this front.

“It’s about making sure equal chance is equal choice for everyone,” Linden says, “because what we’ve realized is that there’s no such thing as equality [in our society] — equal choices don’t exist. We often see politicians talk about making better choices, but all choices aren’t created equal. Some people have much more opportunity than others. And for us, it’s about flattening that and removing barriers so that people have those opportunities and that’s probably set because if we’re looking at actually just some violence.”

Fundamentally, these solutions are aimed at two things: investing in broader societal infrastructure (education, healthcare, housing, employment, etc.) and removing the contradictions inherent in expecting police to be the reactive fix for all of our social problems. After all, how can a traffic stop be performed safely if it is done by increasingly militarized personnel whose job it is is to also confront organized crime? Would this not be the same as putting a traffic officer in the midst of a drug bust? How can we reasonably expect positive outcomes from putting individuals in situations where they are not well-equipped? ‘Providing more training’ at an individual-level cannot solve this – we need to change the institutions that create these situations in the first place.

A blueprint for a world without police

American novelist Ursula K. Le Guin, speaking on the omnipresence of the system of capitalism, stated that, “Its power seems inescapable; so did the divine right of kings. … Power can be resisted and changed by human beings; resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art—the art of words.”

To many, the power of policing seems similarly inescapable. Through effectively communicating strategies of decentralized violence reduction that are separate from police, however, we as a society can build a strategy that both creates jobs and removes the need for police. This communication piece is key, though. One of the failings of broader police reform movements is arguably found in its popular slogans; although ‘defund’ or ‘abolish the police’ are effective rallying cries for opponents to policing, they have been even more powerful mobilizers for police supporters. Opportunists have routinely seized on this power, twisting their messaging to convey a false impression to outsiders that they are intent on destroying rather than creating. It’s hard to organize a movement when public officials can grind your popular support to a halt by labelling you as ‘domestic terrorists’.

Abolitionism, despite what its name and messaging might suggest, is fundamentally about creating rather than destroying. Abolishing the police does not need to be viewed as some radical, ideologically-driven action — it can (and should) rather be framed as an evidence-based method to reducing a bloated bureaucracy, decentralizing public safety and creating more jobs. While this would consist of more funding put towards the issue of violence overall, this funding should be going to proven solutions rather than current models that are both actively harmful in many ways and whose overall effectiveness are inconclusive.

There is a world where violence reduction units could exist and police do not. This approach consists of decoupling police from their responsibilities, honing in on how to best fulfill these responsibilities, and then placing these responsibilities onto the shoulders of sub-specialized units designed to perfect their application. Whether this is in regards to underlying social problems like poverty, crime, or specific police duties like law enforcement or conflict resolution, this piece-meal lens needs to be applied to more aspects of policing.

Just as Will Linden described, we need to do better by getting rid of our current ‘band-aid’ approach to solving violence; investing into alleviating the conditions of violence through policing will not bring about solutions to the conditions that provoke it. By liberating progressive policy solutions from fearmongering and misinformation, we can communicate evidence and move forward toward safer, better functioning societies that don’t include police.

Resources and Further Reading

https://criticalresistance.org/abolish-policing/

https://criticalresistance.org/how-we-organize/

https://criticalresistance.org/organizing-against-policing-overview/

https://communityresourcehub.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/CRH_Alternative_Memo_Final.pdf

https://www.mpd150.com/resources/

https://www.mpd150.com/abolitionreadings-selected-articles/

https://www.mpd150.com/report-old/alternatives/

https://www.mpd150.com/sunset/

https://www.svru.co.uk/about-us/

https://www.svru.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/VRU_Report_Digital_Extra_Lightweight.pdf https://www.researchinpractice.org.uk/media/ajfnocvj/a-public-health-approach-to-violence-reduction_tce_sb_web.pdf

Comments